I started a newsletter because I like to read newsletters. This is my first bit of writing for it. If you want to read about things I love — running, climbing, being a dad, and making a fool of myself, but rarely in that order, you can subscribe here.

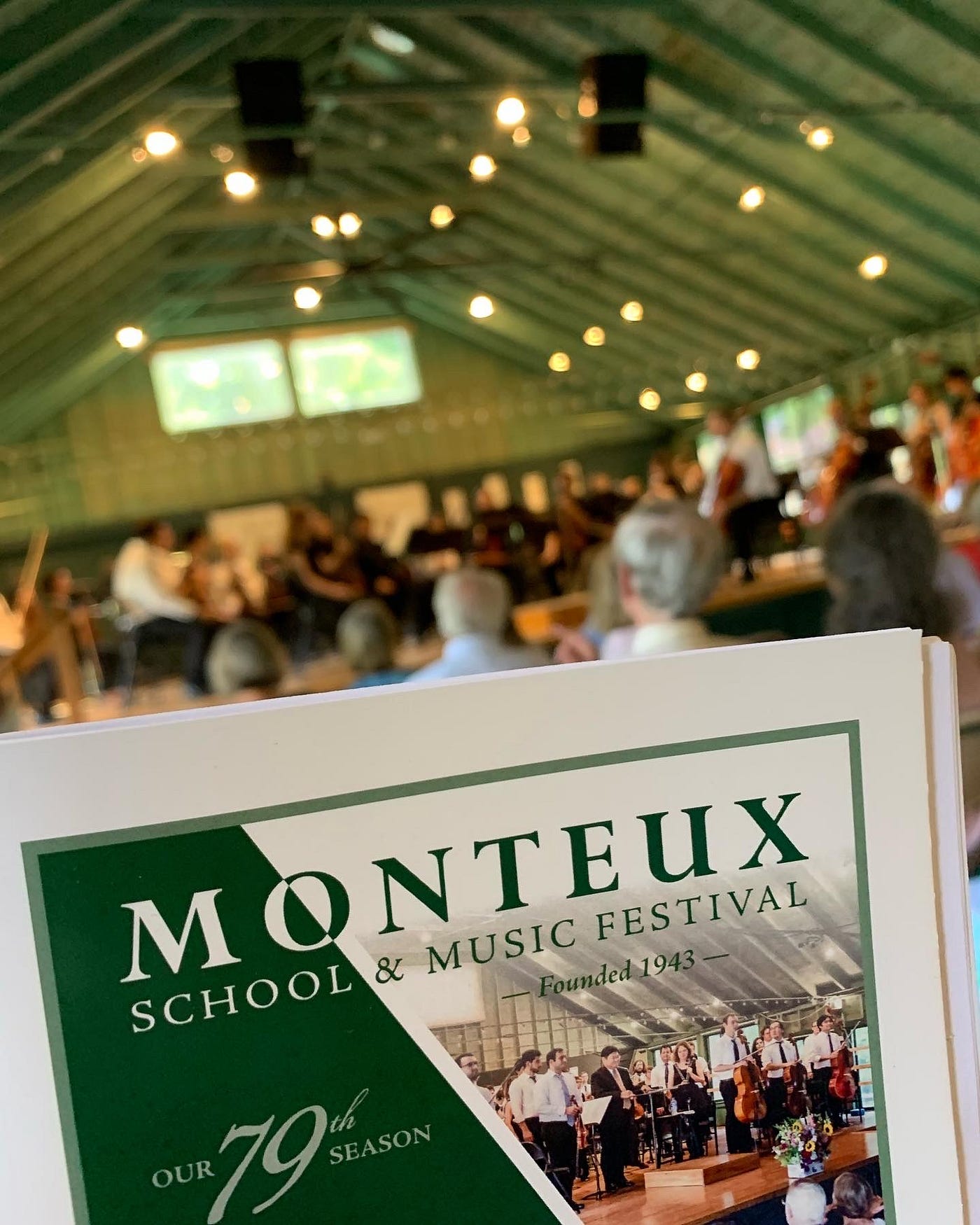

My wife and I took a short trip to Maine to see my daughter perform at the Monteux Music Festival. It’s an amazing program founded by French conductor, Pierre Monteux, in 1942. It’s a conducting school where some of the best young conductors come to train through the summer. Other musicians from around the world audition for spots in the orchestra. They practice hard, live in cabins, form bonds that you can only form when you train hours and hours every day with someone, then party until the early morning and do it all over again. They play a concert every weekend for the locals and vacationers in a beautiful area of Maine near Bar Harbor.

The highlight of the trip for me, aside from the lobster, and Acadia National Park, was listening to the Monteux orchestra perform Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony. If you can, please listen to it as you’re reading this. Here is a good, or at least what sounds good to me performance (for the full immersive effect at no extra cost). My musical ear is not great, and that is what I told the nice grey-haired woman sitting next to me in the small theater in the middle of a forest in rural Maine, but this performance does seem distinctly Russian to me, in a good way.

I asked the woman whose friend recently had my daughter and some of her fellow musicians over for steak, lobster, and far too much wine (which is often the perfect amount) if the orchestra was any good. She was a season ticket holder and patron. She told me that they were great, and they played well together, especially considering the short amount of rehearsal time.

My daughter had shown me the repertoire which was a page of over 50 pieces including symphonies from Mozart, Brahms, Prokofiev, Beethoven, and Tchaikovsky. The woman told me that if I had a good ear, I might hear something a little off. I told her that my ear was not at all good, and I was here to support my daughter. She told me that I would not be disappointed, and really, there is no way that I could, but I wasn’t expecting the overflow of emotion.

The concert started with Debussy’s La Mer and Mozart’s “Overture to Le Nozze di Figaro.” The music filled the building and flowed out the large open windows to the lush forest and mixed with the sound of summer insects and humidity. I especially liked the pre-intermission Mozart. It was familiar like a radio song that you know the words to even if you’ve never consciously played it.

Sophie came and saw us during intermission. She looked beautiful and grown in all black with her hair pulled back. This was my daughter playing beautifully and shining with a light that comes when you are doing something you love. We were connecting with her at her happiest and most fulfilled, and as a parent, there isn’t anything better.

It was a short intermission, and we settled in for the Tchaikovsky. Anticipating some boredom, I read the program and the liner notes for the upcoming symphony. The only thing I knew about Tchaikovsky is that he composed The Nutcracker Suite, and I have had to sit through that multiple times in my life, and I have always been bored with the music. My daughters both performed in the ballet, and I loved watching them dance, but I never connected with the music.

If you have been listening to the 6th Symphony, I hope you’re at the second movement by now. It’s a waltz, and it reminds me of The Nutcracker. It’s light and airy like I imagine a waltz should be, and it reminds me of ruffles and lace dresses. It’s not really for me, but it’s kind of like having a pre-main course of ice gelato in a fancy restaurant that caters to foodies. I mean, who eats ice cream before steak? But it’s a palette cleanser, I guess.

Tchaikovsky was gay at a time and in a place where it was illegal and the punishment could be severe. He also suffered from depression throughout his life. This symphony, the 6th, was his last, and he died nine days after he conducted the first public performance of what he called “the best, and in particular, the most sincere of all my creations.”

There are many rumors surrounding his death. The official line is that he died of cholera, which was common in Russia at the time. However, smart and powerful people kissed his corpse as he lay in state, a questionable choice if he truly died of cholera.

Tchaikovsky struggled with depression his whole life, and he attempted suicide at least once. We don’t know if he died of cholera, succumbed to his depression, killed himself to hide his sexuality, or was convinced to end his life by others whose secrets he was protecting.

I’m at the third movement now. If you’re not there, wait. It’s worth it. It’s a celebration, but knowing what we know about this piece, about Tchaikovsky, and what is to come next, it’s awful and beautiful. It’s set up as a celebratory finale, but there is nothing celebratory about it. With my novice ear, influenced and dulled by years of searing punk rock I hear a mosh pit. It’s that primal feeling of swinging your arms around, hoping to hit something, and get hit by something. Not violence for violence's sake, but an urge, a primal urge to feel connected to others through organized chaos.

I just switched to the concert video and there are some old, gray, tuxedoed clarinetists and there is nothing punk about them, except for the music.

The conductor of the 4th and final movement, “Adagio Lamentoso,” is a small Japanese woman, and my daughter told me she had been subdued when they practiced the piece.

In rehearsal, the guest instructor pressed the conductor to show more emotion, to conduct with passion, and to let go of everything. My daughter told me when she finally did, she sobbed through the piece, letting go of everything, and everyone in the room felt this release. My daughter told me it was one of the most emotional experiences of her life.

It’s not something I can relate to, but I imagine actors, artists, musicians, and anyone who bares their souls as a group and opens themselves up to be torn down or fail in front of others know this feeling. This is something I work to guard against, this opening up to others, and sharing those deep, powerful emotions that we have been taught to hide.

The Tchaikovsky story that I choose to believe is a sad one. It’s depression and living a secret life, and maybe being convinced by himself or others to do something drastic to preserve the illusion. The last movement, preceded by the false finale is a study in sadness. Some audiences clap after the third movement thinking that the piece is over, but the finale is crushingly more powerful.

The orchestra in the middle of the woods performed it beautifully, and I breathed hard, holding in that tightness, that sadness, but there is a part in the middle of the movement where the strings soar, and the conductor lets go, maybe not as much as she did in the safety and comfort of the rehearsal space, but she shared it with the orchestra and the orchestra shared that emotion with us.

We demand that from artists. We expect the conductor, the musicians in the orchestra, and Tchaikovsky to give us their sadness, to bleed for us, and it would be unfair for me to stoically hold my emotion inside. In that movement, I felt a connection to the music, and to my daughter, that doesn’t come easy or often, but when it does, you have to recognize it and be generous with that spirit.

My kids look at me sometimes to see if I’m crying. Usually during a cheesy movie, or a performance, or watching old videos of them when they were younger and didn’t roll their eyes when I asked for a hug. At these moments, I breathe deeper and my heart beats harder as I try to hold back the tears. My youngest daughter will usually say something accusatory like “Dad, are you seriously crying at this?” as we watch some teen drama, and I say “no, but they were just meant to be together” as I wipe the corners of my eyes.

The performance was a lesson. It’s okay to be sad. The sadness connects us. The sadness, the sorrow, the slow lamentation, the silence. Let them flow through you as you listen to that fourth movement. Channel Tchaikovsky’s sadness from more than a century ago, his sorrow, and the silence where you are at once alone and connected, before that storm of applause.

Our world is disjointed and angry, and we have become less connected to each other, to nature, and to ourselves, but sitting in that small concert hall, I was connected to the sadness of the art, the emotions of the artists, and the people around me who come year after year to listen to these young performers give freely of themselves to the point of tears.

The 6th slowly fades out at the end with an almost inaudible drum, and I didn’t want it to end. This moment. There was silence, and nobody clapped. The audience knew. The conductor turned around, spent by the effort, and by the generosity of emotion. And nobody wanted to be the first to clap, but everyone did, and we all did at once. I looked around as we stood up, and this sadness had connected us, teary-eyed with ragged souls, and cheered for the artists with some inadequate form of gratitude.

Thank you for reading this. If you’d like to stay current on what I’m writing about please subscribe to my substack at https://daxross.substack.com/.